Endymion

Review

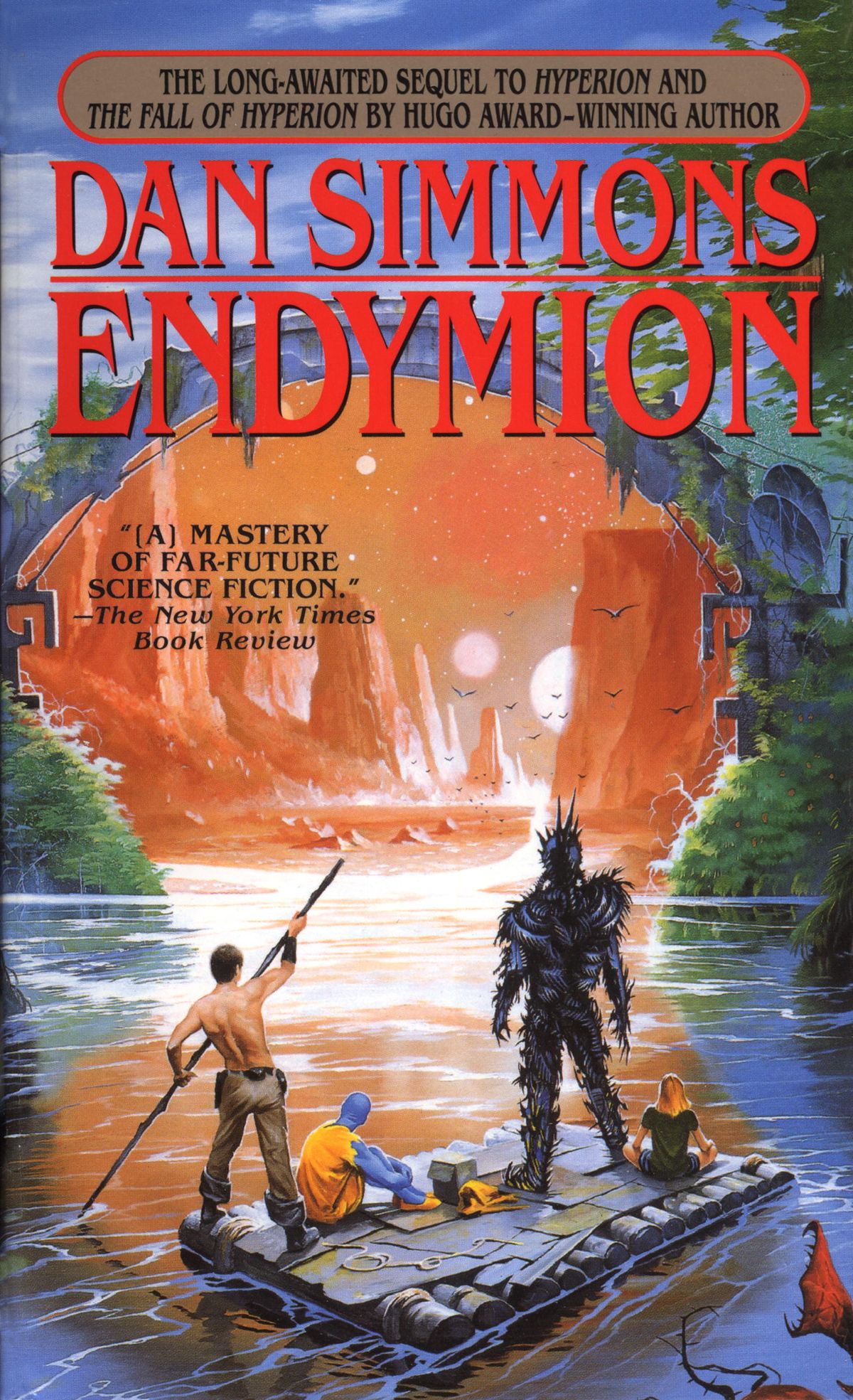

Endymion, by , is the third book in the Hyperion Cantos. It follows a new cast of characters—Aenea, Raul, and Bettik—as they flee the oppressive forces of the Pax via a raft on the River Tethys. Set centuries after the earlier books, the story reveals a galaxy reshaped by the Church and its dark covenant of immortality.

’s Hyperion and The Fall of Hyperion model their plots and themes on ’s Hyperion and The Fall of Hyperion. Endymion follows suit, taking its inspiration from ’s poem of the same name. It is the story of the mortal shepherd Endymion, who falls in love with the moon goddess Cynthia. This relationship shapes both works.

Themes

One of the main themes of ’s Endymion is the pairing of the mortal and the immortal, the earthly and the divine, and we see those same pairings in ’s Endymion as well. Aenea is a messianic figure, a mix of humanity and the divine. The coming Teilhardian human god, created from humanity evolving to godhood, is the same. By contrast, the Pax has given up on the divine and turned to technology, granting immortality through the cruciform parasite instead of true spiritual immortality. Just as in Hyperion and The Fall of Hyperion, things must “die into life”, but the Pax, like the Hegemony before it, has refused death and chosen stagnation.

The story in Endymion follows the structure of Endymion’s journey in the poem, with Raul visiting the underworld (the ice cave of Sol Draconi Septem) and the ocean floor (Mare Infinitus), and meeting Glaucus. It is influenced by other literature as well. The raft voyage itself comes from ’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, with the formerly enslaved android Bettik standing in as a Jim figure. , as he has done throughout the series, also likens his characters to those from ’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Story

There was a lot I enjoyed in Endymion. The nominal antagonist, Federico de Soya, is sympathetic even as he works against the heroes. His slow realization that the Pax isn’t the salvation of humanity he thought it was is haunting. The pacing, once the real antagonist—Rhadamanth Nemes—is revealed, is excellent, and I couldn’t stop turning the pages. The additional worldbuilding, showing how the universe has changed in 300 years, is also really interesting, especially how humanity reacts to true resurrection and the horrifying technology it enables. The freed android Bettik is another great character: searching for his family, unwaveringly loyal and competent, and unfortunately underutilized.

But for all that, this book is good, not great. The pacing is too slow overall: Nemes isn’t even introduced until the last quarter. Raul and Aenea are both annoying—Raul because he spends most of the narrative passive, and then screws things up when he finally acts; Aenea because she is supposed to be a mix of an immature twelve-year-old and an all-knowing messiah, but instead comes off as flipping back and forth between the two. Further, she keeps talking about how she and Raul will someday be lovers, which is uncomfortable given how young she is, and so has to keep throwing in awkward narrator notes reminding us that Raul is not a pedophile and does not find her attractive. At the same time, makes winking allusions to and Lolita.

Literary References

always includes a lot of references to literature and pop culture in his Hyperion Cantos, and this book is no exception. Some of these influences are structural. The raft voyage, as mentioned, is like Huck and Jim’s trip down the Mississippi in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Raul as narrator, writing the story of his and Aenea’s lives with authorial interjections, is like Severian writing his story in ’s The Book of the New Sun. Nemes’s use of monofilament wire to slice the raft in half is a direct reference to a trap used in ’s Stand on Zanzibar, and later reused in ’s The Three-Body Problem. Nemes herself is also clearly modeled on the T-1000 from Terminator 2: Judgment Day: a chrome, shapeshifting, time-traveling assassin sent by a machine intelligence to kill a messianic child, and defeated only after being sunk into molten rock when the previous assassin-turned-bodyguard, the Shrike, fails to stop her in single combat.

Beyond those major influences, there are also smaller moments that reminded me of other works I’ve read. The Pax is similar to Gilead from ’s The Handmaid’s Tale. Its ban on AI is like the Butlerian Jihad from ’s Dune. The Swiss Guard in power armor acts like the Mobile Infantry in ’s Starship Troopers. The Schrödinger’s Cat Box execution method reminded me of the unorthodox execution used on Horza in ’s Consider Phlebas. I loved that androids have “Asimotivation”, modeled after ’s Three Laws from I, Robot. The river journey felt like Ozzy’s trip with the Silfen in Pandora’s Star and Judas Unchained. The A. and M. honorifics to indicate species were similar to the hand gestures used to indicate pronouns in ’s A Mote in Shadow. Being trapped in the ice cave reminded me of being trapped in the nautilus in ’s The Diamond in the Window. The time-travel-based love story is similar to and ’s This Is How You Lose the Time War.

I was tempted to take a break before tackling The Rise of Endymion, which is even longer than this book, but instead I decided to pick it up immediately after finishing. I’m a few chapters into it as I write this review, and I can already tell it’s going to be a struggle. Wish me luck!