The Darfsteller

Review

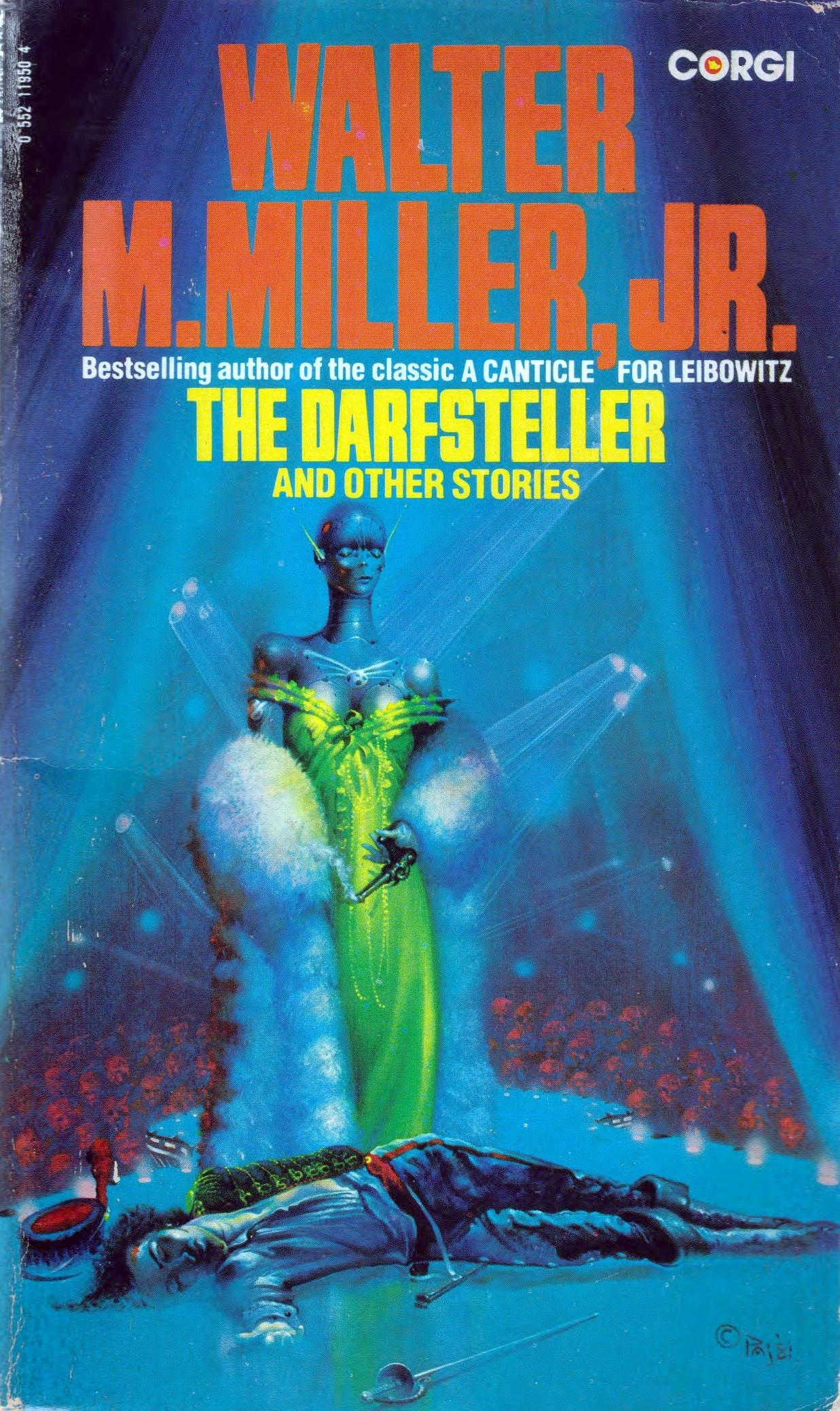

The Darfsteller, by , is a Hugo Award-winning novelette about the obsolescence of the human artist. It follows Ryan Thornier, a former stage idol reduced to working as a janitor in a theater now run entirely by robots and an AI director, as he schemes to take the stage one last time.

In the future of The Darfsteller, actors have been replaced on the stage by robots. An AI Maestro controls them, adjusting the plays on the fly in response to the audiences’ reactions. Audiences prefer the robotic plays because they are easier to understand and less challenging to their views. Against this backdrop, three former actors—Ryan Thornier, Mela Stone, and Jade Ferne—try to figure out what to do with their lives.

Thornier is obsessed with his former life and resorts to mopping the theater floors in a bid to stay close to the stage. When he grows tired of it, and is on the verge of being replaced by a robot yet again, he plots to sabotage the play and give himself one last chance at a starring role. Stone, on the other hand, has accepted the complete commercialization of her art. She sells her personality rights, allowing robots to be made in her image. Ferne was never popular enough for that kind of contract, so she works producing robotic plays instead.

I expected , as an artist, to take Thornier’s side. But he doesn’t, not really. He portrays Thornier as driven by vanity and fighting hopelessly against the inevitable. His inability to respond to the audience and move on makes him more machine-like than the Maestro. Nor does the author condemn Stone and Ferne as collaborators. Even the robots and their creator aren’t villains. If anyone is at fault, it is the audience that has learned to prefer unchallenging plays. But there too, admits this is the reality of how commercial art must be: controlled entirely by economics.

At the end, the author argues that specialists are doomed to be replaced. Only those who keep adapting survive. As one character put it: “The specialty of creating new specialties. Continuously. Your own. […] More or less a definition of Man, isn’t it?” It reminds me of ’s famous assertion that “Specialization is for insects”.1 Although argues more for specializing in being yourself while argues for generalization, both have identified stagnation as the problem.

Science fiction often imagines robots replacing manual labor and AI taking over numerical jobs. A common conceit is that creativity is the one human trait machines can’t emulate, and it is what keeps us relevant. The Darfsteller flips that. Instead, it suggests that creative work will be the first thing we automate. Seventy years later, with the rise of generative AI, that is exactly what we’re seeing. Like current artists, the actors in this story react in different ways: some push back against it while others give in. ’s answer is bleak: in commercial art, what makes money wins. The result feels surprisingly prescient.

The fear of automating creative work is explored in a few other stories, and writers—being writers—have mostly focused on the written word: ’s The Great Automatic Grammatizator features a machine that generates best-sellers automatically; ’s The Silver Eggheads imagines authors selling their names to brand computer-written books; ’s Trurl’s Electronic Bard centers on a machine that writes poetry better than humans, driving them to suicide; ’s Studio 5, The Stars likewise has a poetry machine. ’s Player Piano explores a world where everything is automated. ’s Hyperion tackles the commercialization and debasement of art, where Silenus’s brilliant Cantos flops while his pulpy The Dying Earth sells billions.

Up next is and ’s Monday Begins on Saturday, and then I really should start This Is How You Lose the Time War for my book club.

-

From Time Enough for Love:

A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.