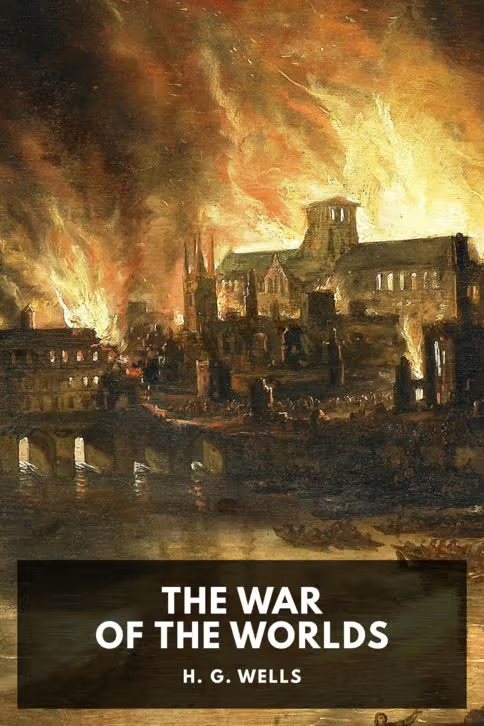

The War of the Worlds

Review

The War of the Worlds, by , is a landmark science fiction novel. It takes place in late Victorian England as an unnamed narrator witnesses a terrifying invasion by Martians with advanced weaponry.

’s The War of the Worlds is a sci-fi classic. It describes the invasion of Earth by Martians and their tripods, the destruction they unleash, and their eventual defeat by bacteria. It was one of the first science fiction books I read as a kid, and it helped shape the kind of stories I’ve loved ever since. It’s hugely influential, having been adapted for radio and film multiple times, including ’s radio drama and films by and .

This book is a version of the invasion novel popular at the time, except that the invaders are Martians instead of European powers. It’s similar to ’s The Battle of Dorking, which kicked off the genre. Both feature surprise attacks on England by technologically superior enemies and are set in Surrey. Woking, where the Martians land, is less than a dozen miles from Dorking, where the climactic battle and the British Army’s defeat take place.

The War of the Worlds is political through and through. It was inspired by the horrors of colonialism and flips the power dynamic: suddenly the English are at the mercy of a greater, indifferent force bent on wiping them out. It also develops several ideas that still resonate. The curate sees the Martians as divine punishment for humanity’s sins, much like some modern Christians see god’s hand in natural disasters. He regrets not using his position to speak out against inequality and the treatment of the poor. The artilleryman, by contrast, sees the Martians as a necessary reckoning—cleansing humanity of the weakness brought on by modern life. That lines up well with a lot of contemporary conservative rhetoric.

But the style of the book makes it hard to love. The prose is great—in a way that House of Suns, Shards of Earth, and The Three-Body Problem are not—but the narrative takes long digressions and slows the pacing as the author focuses on small details. It reminds me a bit of Moby Dick and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, though the digressions are not quite as meandering. Still, those digressions—and the narrator’s journalistic tone—add a sense of realism and immediacy. At the same time, his total lack of agency reinforces the feeling of humanity’s helplessness.

The War of the Worlds deeply influenced how science fiction writers imagined Mars. The idea of ancient Martian civilizations appears in ’s Barsoom series, starting with A Princess of Mars, and in ’s The Martian Chronicles. The tripods and aliens who don’t need to eat or sleep clearly shaped ’s The Tripods series, beginning with The White Mountains and its series prequel, When the Tripods Came. Of my recent reads, the refugee flotilla fleeing the Martians reminded me of ’s The Last Policeman series, especially Countdown City. And of course, the HMS Thunder Child charging in to defend the evacuees brought to mind the ship of the same name facing down the Architects in ’s Shards of Earth.

I first read The War of the Worlds when I was young, and re-reading it now was a nostalgic experience. It makes me want to revisit some of the other authors I loved back then, like , , and , as well as ’s contemporaries like . I’m curious to see how another thirty years of reading and life experience will change the way I see their work.