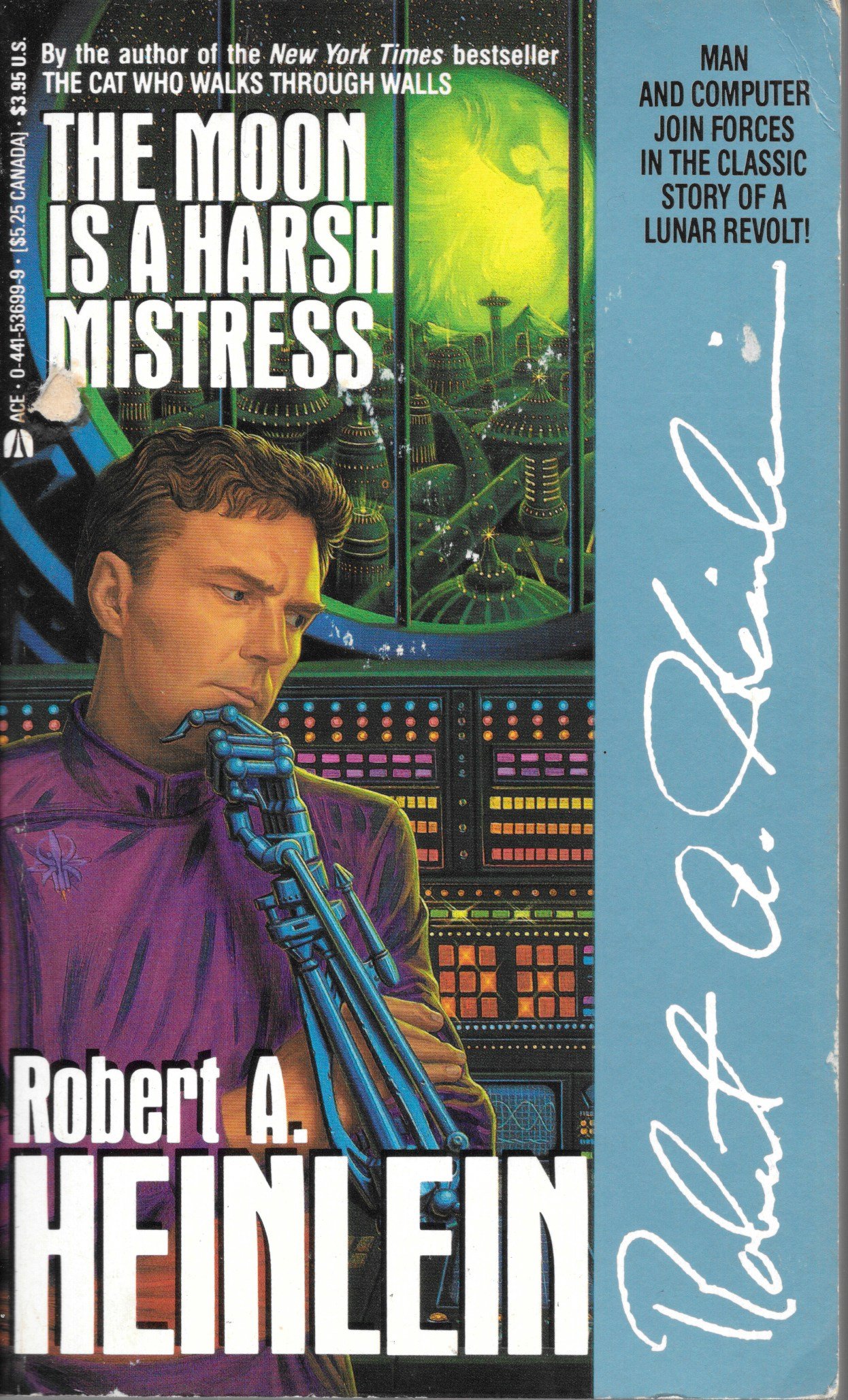

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress

Review

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, by , is a Hugo Award-winning classic of libertarian science fiction. It chronicles the revolt of a lunar penal colony against its terrestrial rulers, a revolution orchestrated by a small group of rebels and their self-aware computer.

I first read The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress about 20 years ago and I loved it. A bunch of plucky rebels, having been pushed around by Earth for too long and with their backs against the wall, decide to declare independence and start dropping rocks down the gravity well until they get their way. And they have a sentient computer backing them up! It wasn’t my first time reading —that was Starship Troopers and Stranger in a Strange Land—but it became my favorite. I even went out and bought a hardcover copy to display on my shelf after finishing the paperback. The only other books I’ve done that for were ’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, ’s The Lord of the Rings, and and ’s Watchmen. I didn’t like The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress as much this read-through.

The story is still engaging, but the long libertarian digressions are much harder to tolerate now. Maybe I was more libertarian-curious in my younger days, or maybe 20 more years of experience has made it clearer how selfish the ideology is. Or maybe the rise of greedy fascism in the modern political climate has soured me on the whole idea. Whatever the reason, I now prefer stories that celebrate community over individualism, like ’s Exit Strategy, to libertarian apologia in the vein of ’s The Probability Broach or ’s The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged.1

For all its lecturing, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress does show some of libertarianism’s warts: lynch mobs, lack of vaccinations killing thousands, the hypocrisy of the “self-reliant” relying on theft from each other. Taxes are theft, but theft is fine, apparently.

The best character is Mycroft “Mike” HOLMES IV,2 the sentient computer named after Sherlock’s brother from ’s The Adventure of the Greek Interpreter. In some ways, he’s a standard sci-fi AI: logical, good with numbers, able to compute probabilities from limited information. But he also behaves like today’s generative AIs: he writes jokes and poems, tries to understand humor, and generates real-time video of his “Adam Selene” persona. Mike raises the classic question of machine consciousness, a theme explored in works like ’s The Murderbot Diaries and ’s Blindsight and Echopraxia, that has become very real with the rise of LLMs. Mike is also the ultimate free lunch, able to oversee the revolution and paid only in companionship and jokes.

The pidgin Mannie speaks mostly reads like the mixed English–Chinese from Firefly, but occasionally the slang sounds off, almost a “codder-shiggy” problem as in Stand on Zanzibar. Also like Stand on Zanzibar, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress deals with overpopulation and environmental collapse, themes that resonated in the late ’60s and were exemplified in and ’s The Population Bomb. The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress tells a revolution story much like ’s Metropolitan, but unlike City on Fire, it doesn’t really explore the aftermath. There’s a quick reference to the professor reading , almost certainly Hyperion. Its theme of a new order overthrowing the old fits perfectly here, just as it did in ’s Hyperion.

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress wasn’t as great as I remembered, which makes me both excited and a little nervous to revisit Starship Troopers—which I loved—and Stranger in a Strange Land—which I hated. I still plan to get back to the Hyperion Cantos with The Fall of Hyperion and the Bolo series with Old Guard, but for now, I’m keeping my break from those going with On Basilisk Station, maybe World Breakers and Snow Crash. And of course, I’ve got to fit in our next book club pick, This Is How You Lose the Time War, too. Hopefully, I’ll get plenty of time to read over the holidays.

-

It’s clear from the above paragraphs which side of John Rogers’s line I fall on:

There are two novels that can change a bookish fourteen-year old’s life: The Lord of the Rings and Atlas Shrugged. One is a childish fantasy that often engenders a lifelong obsession with its unbelievable heroes, leading to an emotionally stunted, socially crippled adulthood, unable to deal with the real world. The other, of course, involves orcs.

-

Highly Optional, Logical, Multi-Evaluating Supervisor, Mark IV ↩