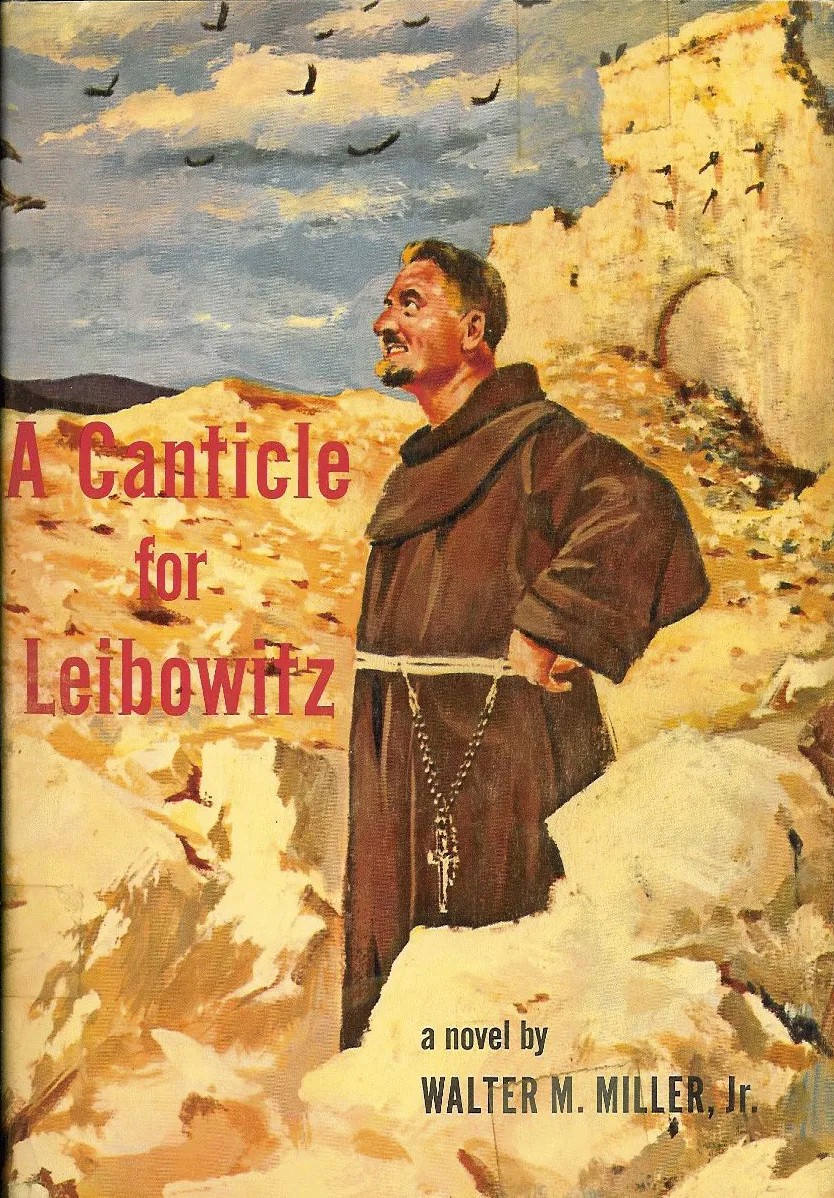

A Canticle for Leibowitz

Review

A Canticle for Leibowitz, by , is the first book in the Saint Leibowitz series. It is a fix-up novel consisting of three parts: Fiat Homo, Fiat Lux, and Fiat Voluntas Tua. The story follows the monks of the Albertian Order of Leibowitz as they preserve the remains of humanity’s knowledge after an atomic war.

The major theme of the book is the cyclical nature of humanity’s fall and the question: “Are we doomed to repeat it?” Other themes include the conflict between faith and reason, the double-edged sword of knowledge, and the nature of suffering and sin.

It is an explicitly Catholic book, if that wasn’t clear from the fact that it’s about monks. In that way, it reminds me a lot of ’s The Book of the New Sun and ’s Hyperion. All three authors mix Catholic theology with science fiction, but it goes deeper than that. They share a Catholic worldview: institutional faith is central, pain and suffering are core themes, and their far-future worlds feel ancient and burdened by the past.

Fiat Homo

Hundreds of years after the “Flame Deluge” destroyed civilization, a young novice named Brother Francis Gerard discovers a fallout shelter containing relics—a shopping list, a blueprint, etc.—from his order’s founder: the Blessed Leibowitz. Abbot Arkos worries the serendipitous discovery will disrupt Leibowitz’s canonization, but he can’t dissuade Gerard’s obsession. Gerard spends 15 years creating an illuminated version of the blueprint before having it stolen on his journey to New Rome to witness the beatification of Leibowitz. He is killed by mutants on the way home.

In this section, we see civilization beginning its cycle again. We also see the smaller cycles works into his stories: Gerard’s repeated encounters with the buzzards, who finally eat him, and the way the Wandering Jew both starts and ends the section.

Fiat Lux

Hundreds of years later, humans are starting to build empires again. Thon Taddeo, a scientist and heir to the Texarkana kingdom, visits the Abbey to study the Memorabilia. Some monks are also studying the old texts and use them to invent an arc lamp. Abbot Paulo is caught between the rise of secular power and knowledge, and the mission his brotherhood has upheld for hundreds of years.

The clearest theme is the tension between religion and science, with the monks not fully trusting the Thon, nor their own Brother Kornhoer, who invents the lamp. The theme also shows up in the Church preparing to physically defend itself from the state, which wants to use it as a fort in its conquest of the plains, and Taddeo’s refusal to take responsibility for his cousin’s use of science in war.

In this section, Taddeo wonders if humans are the servants of a higher race that created them, based on a piece from the Memorabilia—a reference to the play R.U.R. by .1

Fiat Voluntas Tua

In the far future, humanity has once again conquered the atom and is on the brink of war, taking us full circle back to the beginning of the book. Abbot Zerchi prepares some of the brothers for a trip to human colonies in the stars to preserve the Order while waiting for nuclear annihilation on Earth.

continues the theme of conflict between the realm of man and the realm of God, much more openly. Abbot Zerchi spends pages arguing with a doctor about whether people should be allowed government euthanasia after receiving a fatal dose of radiation. The Abbot, following Catholic doctrine, says no under any circumstances. Zerchi eventually has the argument again with a woman and her child who are dying of radiation poisoning. Knowing as we do now that eventually committed suicide, the argument feels less like a theological exercise and more like a man trying to steady himself with his own faith.

At the end, the nuclear war resumes and Zerchi is trapped when the church collapses. The two-headed mutant Mrs. Grales finds him—except her child-head, Rachel, is in control. He realizes that Rachel was born without sin when she rejects his attempt to baptize her and instead administers the Eucharist to him.

Rachel is an interesting character, despite her short time in the story. She is a new Eve, representing the start of the cycle again. She embodies the Mary archetype, which Zerchi recognizes when he begins praying the Magnificat—the canticle Mary spoke when she visited Elizabeth in the Bible. She is also a Christ-like figure: she was born of Mrs. Grales alone; humanity’s temptation to give in to euthanasia, and Zerchi himself trapped and dying in agony, can be interpreted as the Apostasy that Catholics think will precede Jesus’s return. Rachel arrives right before humanity destroys itself again, necessitating the final judgment.

In a way, Rachel also reminds me of Athena. Both sprout from their parent, both are virginal, and both are symbols of knowledge. But while Athena is tied to civilization and war—she is born fully clothed and armed—Rachel is a being of “primal innocence” and represents a return to Eden.2 Once again it’s the theme of secular versus spiritual knowledge, but this time Rachel signals the end of the age of Athena.

Legacy

asks, “Are we doomed to repeat the fall?” A Canticle for Leibowitz’s answer is “yes”. Humanity first fell when they were banished from Eden, after the serpent promised Adam and Eve knowledge of good and evil. The second fall was the “Flame Deluge”, the nuclear war that scoured the earth right before the novel takes place. And the third comes at the end of the book, when humanity loses Earth.

I really enjoyed A Canticle for Leibowitz. Fiat Homo is a little slow, but Fiat Lux does a great job capturing a moment from the Abbey and the wider world, with the courage to end the section without over-explaining. And Fiat Voluntas Tua brings a growing sense of dread for the coming war while echoing and reinforcing the themes from earlier in the book, bringing the cycle back around one last time.

You can see the influence of A Canticle for Leibowitz all over the genre. The Brotherhood of Steel in Fallout is similar to the Order, preserving technology after a nuclear war. There is also the Adeptus Mechanicus from Warhammer 40,000, who use sacred rituals to preserve technology and, like Abbot Zerchi, refer to AI as “abominable”. A religious order preserving knowledge is also the key plot point in ’s Anathem.

Mad Bear in Fiat Lux reminds me of the Lord of the Mountain from ’s Ancestral Voices and The Sixth Sun. The general post-apocalyptic fantasy world had a similar feel to ’s Sword of the Spirits. The dread of the coming nuclear war in Fiat Voluntas Tua made me feel the same way I did when reading ’s Cthulhu Mythos inspired A Colder War.

I don’t know if I’ll read the sequel, Saint Leibowitz and the Wild Horse Woman, which was published after the author’s death and half written by . The reviews are mixed, and I worry it will be an unnecessary coda, like The Urth of the New Sun was to The Book of the New Sun. But I will be reading ’s The Darfsteller shortly. It’s a novelette about machines replacing humans in the arts, which couldn’t be more timely with the release of Generative AI. Before any of that though, I’m going to read the new version of ’s There Is No Antimemetics Division which just released. I’m looking forward to it!

-

R.U.R. is the origin of the word “Robot”. ↩

-

He did not ask why God would choose to raise up a creature of primal innocence from the shoulder of Mrs. Grales, or why God gave to it the preternatural gifts of Eden—those gifts which Man had been trying to seize by brute force again from Heaven since first he lost them.